Tenet 6.7: Health 3.0 is Antifragile – Skin in the Game of Health Care.

I’m naked and exposed now. And that’s the way I want it to be.

After running my gastroenterology practice under the traditional insurance model for over ten years, I came out of all insurance networks in April 2016.

It was a tough decision. One that lost me referrals from the many primary care colleagues still operating in the traditional model…patients who won’t see anyone not on their insurance plan…and revenue from what those insurances paid me.

Now I’m on the entrepreneurial edge. Hardly any other gastroenterologist around the country is doing what I’m doing. But if I don’t serve my community with true value, month in and month out – I’m out of business.

That’s my skin in the game.

Skin in the game is the last concept on how we make health care more antifragile. But it may be the most important.

Nassim Taleb discussed skin in the game in Antifragile. It’s so important for him, it’s the name of his upcoming book.

Here is Taleb’s definition, in Skin in the Game: “No words count unless those who utter them are exposed to their costs (should there be any), and share some of the consequences with those who are affected by the actions.”

Skin in the game is the great equalizer. As Taleb relates, an engineer of a bridge can hide corner-cutting measures that won’t significantly increase the risks of the bridge collapsing. But he won’t do it if he has to live under his bridge. His head is on the line.

Taleb believes the biggest cancer of modernity is the increasing lack of skin in the game.

Internet bloggers, journalists, politicians, bankers, Wall Street CEOs, and academics alike are inoculating themselves in their respective industries. They get to do what they want and get benefits while others pay the price, often unknowingly. In effect, they transfer their fragility to others.

The medical industry is no exception to this trend.

Health 2.0 is trying to get more health care provider skin in the game by emphasizing value over volume. First, through incentives like sharing cost savings via accountable care organizations (ACOs). But eventually, through penalties for not meeting health care mandates.

But this top-down approach is fragile. The more middlemen we have between the doctor and the patient, the more they can game the system. They have no skin in the game, because they don’t answer directly to the patient.

And the middleman will make out as the most antifragile stakeholder in this game. At the expense of the rest of us.

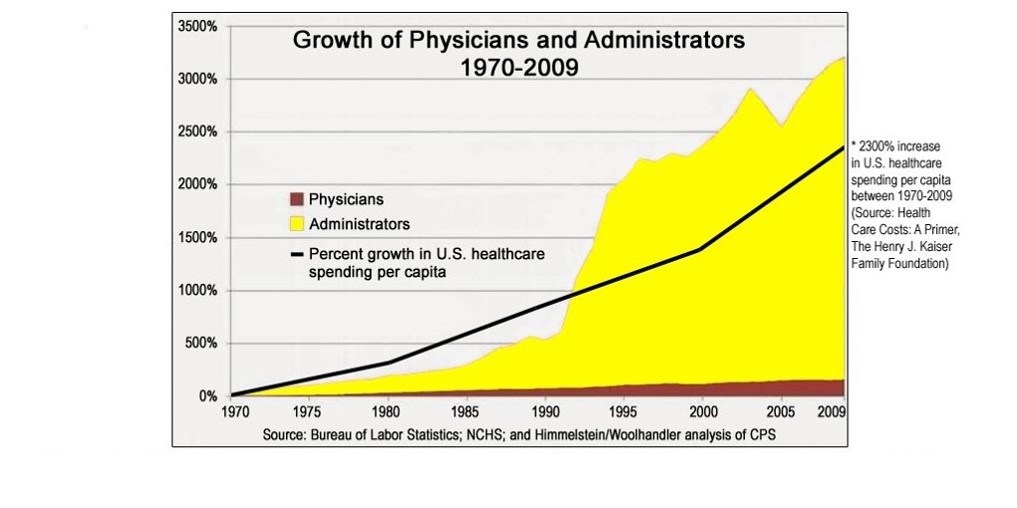

Look at the chart above. From 1970 to 2009, there’s been an over 3000% increase in health care administrators in America! This dwarfs the increase in doctors.

This explosion in administrators has only accelerated with Obamacare. When you have thousands of pages to decipher in the ACA, you get thousands more administrators.

These administrators talk a big game. Many of them make hundreds of thousands of dollars more than physicians.

But what skin do they have?

In the same 1970-2009 period, there’s been a 2300% increase in U.S. healthcare spending per capita. Have they been exposed to those costs? Have they borne the consequences of those affected by their actions?

In Antifragile, Taleb rails against people like Robert Rubin who represent the incestuous relationship between government and industry. As secretary of the Treasury, he helped put in place rules that he could later exploit as head of Citigroup. Then he received $120 million in bonuses while the Treasury bailed Citigroup out.

He won. We taxpayers lost.

Our health care industry has similar relationships.

Take the example of Dr. Farzad Mostashari. Mostashari was the health information technology (IT) czar at the Department of Health and Human Services. He was a key figure in promoting “meaningful use” in health care – which I argue was really meaningless abuse for many independent physicians. I applaud him for the tall task of bringing technology into medical records and championing interoperability and continuity of access to medical data.

But his opinions on the problem of consolidation in health care ring hollow. His very actions as health IT czar forced many physicians with small practices to consolidate with hospitals, or close up shop altogether.

Now…he’s running a company called Aledade that raises $75 million and gets a glowing article in The New York Times about how he “wants to save the independent primary care doctor, whose practices have been battered by the perverse incentives of the American health care system”?

Now…he writes articles called “The Paradox of Size: How Small, Independent Practices Can Thrive in Value-Based Care”?

Now…his colleague and another government-turned-industry warrior, Dr. Bob Kocher (who sits on the board of Aledade), writes an op-ed piece on how he was wrong about Obamacare?

Now…Mostashari wants us “…to lean in and dig your paddle in and push ahead…increase your power, increase your control, increase your ability to have someone else help you deal with that crap, deal with the quality reporting, deal with the EHR optimization, deal with the ACO regulations…not to retreat into some direct primary care model”?

Let me get this straight. Kocher and Mostashari can push – by fiat – consolidation, health IT, and meaningless abuse metrics that measured nothing of value and could easily be gamed by anyone with half a brain, break the backs of independent, conscientious practitioners who burned out or were swallowed up by the big boys in the name of “quality,” make these byzantine rules while in the public sector, come out to the private sector, write op-ed pieces attracting people to them with click-bait headlines like “How I Was Wrong about ObamaCare,” and then sit on the boards of companies while working the loopholes in rules that only they know? At no cost to themselves for this clusterf*#$?

Dr. Mostashari, you yourself called it “crap.” It’s your crap! Why do we have to deal with it? Or have to now hire your company, Aledade, to deal with it?

Dr. Ryan Neuhofel, a family physician who’s been running a direct primary care (DPC) practice in Kansas and knows many other DPC physicians, said it well in response to Mostashari:

These DPC physicians are among the most courageous, creative and determined men and women I know; the exact opposite of what you describe. They have each taken huge risks — professionally, personally and financially — in an attempt to “take control” as you suggest. Most have sacrificed hundreds-of-thousands of dollars in pursuit of becoming the caregivers they envisioned while in medical school.

Out of necessity, they are educating their communities on the importance of quality primary care. They hold town halls and talk to the media. They network heavily with technology and medical vendors. They engage employers and policy makers. They write blogs and vigorously in online discussion groups. They are the epitome of entrepreneurship and activism.

The DPC physicians I’ve met nearly always possess a passion that has sadly been beaten out of most of my physician colleagues. Despite giant obstacles and an uncertain future, DPC physicians forge ahead. Our vision for the future of primary care may be naive to you Dr. Mostashari, but to claim we are passive or “retreating” is flatly absurd.

I do agree that a major driving factor behind the DPC movement is physicians feeling powerless to deal with an ever-growing pile of “crap.” Can you blame them? Older physicians have lived through many decades of initiatives purporting to improve the practice of primary care — only to realize the newest barrage of alphabet soup was keeping them even more distracted from patient care. Is it possible to outsource some of that administrative burden? Sure, but physicians are rightfully skeptical about why the “crap” exists in the first place.

Being born and raised in Kansas, I admittedly don’t know much about kayaking. However, I would suggest that the rapids have already tipped over many of our boats. Direct primary care physicians have bravely climbed back in their vessels and are now trying to rescue others; hopefully, before we all go over the waterfall.

It doesn’t matter if you believe in direct care or the insurance model. This goes beyond left or right, liberal or conservative. The administrative-political-industrial complex has infected our health care system. The fundamental problem with this is a complete lack of skin in the game.

But it’s not just about administrators, politicians, and industry heads. We as physicians have have to check in with ourselves, about our own level of skin in the game. I’m not talking about something like hospital administrators pressing doctors to have skin in the game with work incentives. Those are performance measures, not skin in the game – and may be bad ones at that.

The question is, are we as doctors putting something at risk ourselves, or we owning an upside option at someone else’s expense?

I recently attended a lecture by Dr. Eduardo Salas on the science of teamwork in health care. He’s been successful in getting the military and airline industry to adopt teamwork in their domains. But in the lecture Salas said that he’s had a harder time getting health care organizations to play ball – even in the face of data showing better performance and outcomes.

There are likely a number of reasons for this, but I think a big one is skin in the game.

If a Navy Seal isn’t optimizing for peak performance, he’s dead. Same with an airline pilot. If something goes wrong, not only will the passengers go down – so will the pilot.

That’s the ultimate skin in the game. We as physicians don’t have that level of skin at risk. If a patient dies, we don’t.

I’m not saying we need to die. But there is an asymmetry there. We may have more at risk than an administrator (by way of our malpractice liability, our reputation, and our conscience from being the ones directly connected to our patients). But if we want to remain Health 1.0 cowboys without communicating as a team involved in a patient’s care…or if we want to hide behind as cogs in a Health 2.0 machine without stepping up as leaders on the team – then we have to bear some cost if things go wrong.

A lack of skin in the game like this runs rampant in our current healthcare system. From administrators to politicians to industry analysts to doctors, no skin in the game means compromised patient care.

And when the system divorces the true cost of health care from the patient himself, who isn’t asked to invest in it upfront – that may be the biggest lack of skin in the game of them all. Who is the sucker here? The taxpayer, to be sure. But also our whole society.

All of us deserve a safety net to cover us for catastrophic healthcare. But all of us are also responsible for our health, with whatever best tools we create together.

As I finish this tenet of Health 3.0, that Health 3.0 is antifragile, here’s a major heuristic: Any ideas put forth in Health 3.0 don’t count without skin in the game.

That goes for you, and for me.

Dr. Julapalli,

Having skin in the game means you got to have your neck on the chopping block as much as the next guy. But who wants their head on a chopping block? It is much easier to give lip service and play the role of the armchair quarterback come Tuesday morning. Having skin in the game is hard work, makes folks feel vulnerable and exposed (as you’ve put it), and forces them to be accountable to themselves and all the other players.

Please allow me to be little facetious here.

First of all, change is never easy. I pay for insurance through my employer. If I go to someone out of network, I am penalized and have to pay more out of pocket. If I go to a doctor that does not accept my insurance, then I have to shoulder the entire cost, and whatever I spend out of pocket does not even put a dent in my high deductible. It seems it would be easier for me to look for a doctor on the list of healthcare providers who have agreed to work with my plan. That is the way I have always done it, so why change now? Is it important to me that my doctor is under great pressure to stay afloat in his practice by ordering more tests and scheduling more visits?

Secondly, I am totally ignorant of the rigmarole of billing, fee schedules, coding system or what have you. I just know that the office is going to bill my insurance and then whatever insurance does not cover come out of my pocket. Sadly, price shopping for healthcare services is not as easy and as accessible as checking the Sunday circulars for the best price on chicken breasts. So, I roll with the flow and pay the cost. Having said all this: Doctor Julapalli, you are the only doctor (I know of) that is cost transparent.

Thirdly, I am not seeing myself as the most important player in my healthcare. I get sick, I go to the doctor, I expect him to put me back together again. Despite his best efforts, no amount of treatment or care will bear fruit without my willing to modify my lifestyle and monitor progress. So do I care that my lack of involvement in my own care may reflect badly on my doctor? I don’t know, that is his problem. Do I care that my poor lifestyle choices ultimately contribute to higher insurance and healthcare costs for all? Does little old me have that much influence over insurance market?

Dr. Julapalli, you are not kidding when you say that you are naked and exposed. You are taking on a lot here. More than a mouthful. You are bucking the system. So I guess that makes you a pioneer (or one of the pioneers) in a movement to reform the status quo.

You are taking on all the players.

I wish we could run healthcare like Jeff Bezos runs Amazon. I don’t know what makes Amazon so successful, but I know I love doing business with this company. And everyone else I know loves Amazon just as much if not more. Some even refer to themselves as “Amazon girls.” For one thing, Amazon takes customer service seriously. They respect their customers. Customer loyalty is everything to them and they fight hard to keep the business. They make the customer feel as though he or she is special; individualizing service.

But then maybe we can!

When Bezos started Amazon, there was a lot of eye-rolling and lifting of the eyebrows. Folks wondered who this Johnny-come-lately think he is for wanting to compete with Barns & Nobel. But he took on the status quo and never looked back.

And, Dr. Julapalli, that is exactly what you are doing. You are taking on the status quo. You are the Jeff Bezos of healthcare!!!!

Bravo for having the guts to say what a lot of us have been thinking! I’m in the process of switching doctors for that very reason – I’ve seen what happens when a doctor capitulates and joins a major health care syndicate. I trusted this doctor when he was a private practitioner – I’m not sure I do now. Keep it coming!

You’re absolutely right, the administrative-political-industrial complex has infected our health care system, not just in US but all over the World. Every 5-10 years we get so called initiatives that suppose change everything to better and we shouldn’t even think about them, our job is to be aligned.

If doctors and patients continue to live in a shadow we won’t change anything, for 20 years we will have HealthCare 6.0 which will be worse than HealthCare 0.0.

Skin in the Game is a crucial. We need to become independent and responsible for what happens, it’s the only way.